posted 2nd September 2024

A Horrible History of Theatre in Exeter

Exeter was a theatre pioneer from the 14th century to the end of the 19th, when the destruction by fire of the Theatre Royal prompted the government to bring in fire safety standards that remain in place today. Some of the key players and themes were:

The Brotherhood of Brothelyngham: a real group, but whether they were independent street entertainers, semi-official fund-raisers for local parishes or just a gang of hustlers is somewhat open to interpretation. That they were picked out for condemnation by Bishop Grandisson is not in question however. They were led by an “abbot”, who may have been the guiding intelligence or just an exploited front.

The Robin Hood plays: a staple of rural and urban entertainment throughout the 15th century and well into the 16th throughout England, usually performed in May. They have definite roots in fertility rituals, but also contained many of the stories of Sherwood that we all know. The first recorded performance was in Exeter, but that script is lost.

The Exeter Cycle of Mystery Plays: a tempting prospect, but it was probably not as big as the Wakefield or York cycles which are the only ones we now have. Certainly the Guild of Skinners did organise an annual set of performances on Corpus Christi, which ceased when the City Council, who paid for it, wanted to move the date and the Skinners refused. The scripts were then lost.

Travelling Players were a fixture from the middle of the 16th century and there are substantial records of the various London companies visiting Exeter and Devon on many occasions. Most of the big companies came – often when the plague closed the London stages, and they usually played in the Guildhall.

Andrew Brice (1690- 1773) is the shamefully unknown father of the permanent theatre in Exeter. A newspaper proprietor and persistent quarreller with authority, he devoted much time, effort and money to establishing the first regular theatre (in the Seven Stars Inn – then by the Exe Bridge) and the first purpose-built theatre behind the Guildhall.

Edmund Kean (1787-1833) was the biggest theatrical star of his generation. He dazzled in Shakespeare’s big roles, but also in a range of dramas, farces and comedies, and often played Harlequin in pantomime. He spent two years in Exeter at the beginning of his career, and came back later once he had conquered London society at Drury Lane. His behaviour, fuelled by alcoholism, was frequently appalling.

Theatre Fires were an occupational hazard once lighting and scenery became the norm. Lanterns were hot, with open flames, and very little was fire-proofed. Theatres were often jammed with people, had no safety regulations or precautions whatsoever to start with and burned down regularly. Of the three Exeter Theatre Royal fires which entirely destroyed their buildings, fortunately only the last one caused loss of life. There was a string of fires in the 19th century throughout Europe – St Petersburg, Karlsruhe, Nice, Paris etc – with death tolls in the hundreds.

The Exeter Theatre Royal Fire of 1887 was the direct cause of theatre safety licensing in this country. Appalled by the unnecessary loss of life, the Government and Local Authorities finally drew up a set of laws to mandate unlocked doors which opened outwards, alternative escape routes, safety curtains and dual lighting systems. Only the London Royal Warrant theatres – at Drury Lane and Covent Garden – were exempt, and they continued to ignore them.

Captain Sir Eyre Massey Shaw (1830-1908) was the commander of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade. He attended the Exeter inquest (held the week after the disaster) and 22 days after the fire submitted a report which formed the basis for all the safety changes which came afterwards. At this time he was already famous enough to have been named directly in Iolanthe, the G&W operetta.

William Topaz McGonagall (1825-1902), often called Britain’s worst poet. Best known for his Tay Bridge Disaster, McGonagall was quick to respond to the Exeter fire with his typical brute force lyricism, a stranger to scanning and the poetic use of language.

Review

Review by Julie Rashbrooke

As Estuary Players celebrates 45 years of performing, few amateur companies would take on the challenge of creating a full length, original piece of theatre, with music and song. Like a House on Fire was written by Alan Caig, who also directed. This follows on from the great success of The Final Cut, which also played at Matthews Hall in 2019 and later in various outside venues, including Powderham Castle. This time Alan wanted to tell the story of theatre in Exeter, from the earliest recorded accounts in the Middle Ages through to the catastrophic fire at the third Theatre Royal in the city.

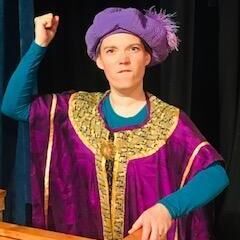

The play started with the whole company singing at the back of the auditorium before the revels began with The Brotherhood of Brothelyngham, cavorting on stage - a real group of players that performed in Exeter in the Middle Ages. The whole story was told with comic effect through dialogue and song by the whole company, with different members of the group taking on the lead and changing roles. There were some outstanding solo and small group performances as well as great ensemble playing.

Following extensive research, Alan had a huge amount of material to draw from, so deciding what to leave out, as much as what to include was required, to ensure it succeeded as a piece of live theatre. He chose to focus on key parts to tell the story of theatre in Exeter. This included the Exeter Miracle Plays, which may not have survived like those of York, but were still part of the development of theatre in the city. These were followed by the Robin Hood plays, performed throughout England in the 15th Century, with their roots in fertility rituals as well as tales of Sherwood. The play showed then how in the 16th century travelling players, including many big companies, visited Exeter, particularly during the plague when London theatres were closed.

The audience was introduced to Andrew Brice, a newspaper proprietor, who established the first regular theatre in Exeter behind the Guildhall. And the charismatic, but badly behaved Edmund Kean, the most famous actor of his generation, was portrayed with comedic effect by Rachel Ratibb. Kean had visited Exeter before and after conquering the London stage.

The climax of the play is of course “the house on fire’’, which showed how all three of The Exeter Theatre Royal theatres were burnt to the ground, with the last catastrophic event leading to a huge loss of life and subsequently a change in the laws governing all theatres, apart from Drury Lane and Covent Garden in London. These changes resulted in the introduction of the Safety Curtain, escape routes and other measures. Following hundreds of lives lost in theatres throughout Europe during the 19th Century it was hoped these new safety measures would stop this from happening.

It's not an easy task to make such a tragic tale of loss into an engaging and comic piece of theatre. However, the cast were able to tell this historic and important story, informing as well as entertaining the audience. I expect many, like me, knew little about the events told and enjoyed discovering the facts whilst enjoying the performance.

As well as an accomplished script and talented actors this production benefited from original music written by Mark Perry. And it was good to have some live music on the night provided by Ian Dodds on the keyboard. There were nine songs in the production, and I particularly liked the amusing Marketing song performed by Keith Palmer, David Batty and Howard Eilbeck.

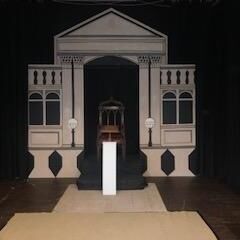

Transforming Matthews Hall into a performance space, local artist, and designer Phil Keen, created a wonderful backdrop. Phil is well known for providing amazing scenery for Estuary Players and he didn’t disappoint this time. The addition of a thrust to the front of the stage enabled the director, and Clare Philbrock as choreographer, more space to create an effective staging of the piece. This enlarged the stage area, reached into the audience, and greatly enhanced the production. With limited equipment available, the lighting, by Ed Rashbrooke, also added to the atmosphere.

I particularly liked the use of textiles, created by Janine Warre, to represent fire on stage as well on the screen and around the stage area. Janine was also responsible for the huge array of costumes worn by the cast in the show.

No production can succeed without all the backstage people which included, Jackie Jennings as Stage Manager, Chris and Howard Elbeck on Box Office as well as the front of house team.

And last but not least, special mention to McGonagall. Looking very dapper in full Scottish attire-he provided some very funny moments and much laughter from the audience each time he came on stage and attempted to recite a poem, only to be pushed off the stage by other characters. Eventually he was allowed to finish his poem, ‘The Burning of the Exeter Theatre’, to considerable applause.

It was good to see some younger members of the players join more established actors, and especially welcome to see such inclusive casting, including Maggie Butt, one of the founder members of Estuary Players who was performing for the last time. It’s obvious just how much this theatre group means to all those who take part and those who come to watch.

It would be lovely if this story could be developed further and given a wider audience.

And wouldn’t it be wonderful if the centre of Exeter got a fourth, purpose built, Exeter Theatre Royal-as long as it didn’t get burnt down this time!

Cast and Crew

Company:

Marie Watsham, Lynn Trout, Ian Potts, Clare Philbrock, Keith Palmer, Lynn Leger, Sam King, Howard Eilbeck, Chris Eilbeck, Bob Drury, Suzanne Dunstan, Becky Davies, Rachel Cooper, Alan Caig, Maggie Butt, Margaret Bond, David Batty

Production Team:

Alan Caig: Direction, Script, Lyrics

Mark Perry: Original Music

Janine Warre: Production Management, Costume Design

Phil Keen: Production Design

Ian Dodds: Piano

Clare Philbrock: Movement, Additional Material

Ed Rashbrooke: Lighting

Chris and Howard Eilbeck: Box Office

Rosie Munns and members of the company: Front of House

Tim Pratt: Lighting Rigging

Jackie Jennnings: Stage Management